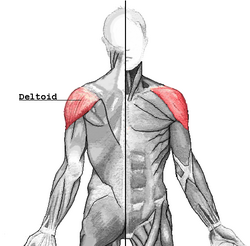

Deltoid muscle

| Deltoid muscle | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Deltoid muscle | |

|

|

|

| Muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column. | |

| Latin | musculus deltoideus |

| Gray's | subject #123 439 |

| Origin | the anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle, acromion, spine of the scapula |

| Insertion | deltoid tuberosity of humerus |

| Artery | primarily posterior circumflex humeral artery |

| Nerve | Axillary nerve |

| Actions | shoulder abduction, flexion and extension |

| Antagonist | Latissimus dorsi |

In human anatomy, the deltoid muscle is the muscle forming the rounded contour of the shoulder. Anatomically, it appears to be made up of three distinct sets of fibers though electromyography suggests that it consists of at least seven groups that can be independently coordinated by the central nervous system.[1]

It was previously called the Deltoideus and the name is still used by some anatomists. It is called so because it is in the shape of the Greek letter Delta (triangle). It is also known as the common shoulder muscle, particularly in comparative anatomy (e.g., in lower animals).

The deltoid is a frequent site to administer intra-muscular injections and vaccines.

A study of 30 shoulders found it weighs around 191.9 g (range 84–366 g) in humans.[2]

Contents |

Origin

It arises in three distinct sets of fibers:[3]

- Anterior fibers: from the anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle.

- Middle fibers: from the lateral margin and upper surface of the acromion

- Posterior fibers: from the lower lip of the posterior border of the spine of the scapula, as far back as the triangular surface at its medial end.

Insertion

From this extensive origin the fibers converge toward their insertion, the middle passing vertically, the anterior obliquely backward and laterally, the posterior obliquely forward and laterally; they unite in a thick tendon, which is inserted into the V-shaped deltoid tuberosity on the middle of the lateral aspect of the shaft of the humerus. At its insertion the muscle gives off an expansion to the deep fascia of the arm.

Innervation

The deltoid is innervated by the axillary nerve. The axillary nerve originates from the ventral rami of the C5 and C6 spinal nerves, via the superior trunk, posterior division of the superior trunk, and the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.

The axillary nerve is sometimes damaged during operations on the axilla, such as for breast cancer. It may also be injured by improper use of crutches.

Action

When all its fibers contract simultaneously, the deltoid is the prime mover of arm abduction along the frontal plane. The arm must be internally rotated for the deltoid to have maximum effect. This makes the deltoid an antagonist muscle of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi during arm adduction.

The anterior fibers are involved in shoulder abduction when the shoulder is externally rotated. The anterior deltoid is weak in strict transverse flexion but assists the pectoralis major during shoulder transverse flexion / shoulder flexion (elbow slightly inferior to shoulders).

The posterior fibers are strongly involved in transverse extension particularly as the latissimus dorsi is very weak in strict transverse extension. The posterior deltoid is also the primary shoulder hyperextensor.

The lateral fibers are involved in shoulder abduction when the shoulder is internally rotated, and are involved in shoulder transverse abduction (shoulder externally rotated) -- but are not utilized significantly during strict transverse extension (shoulder internally rotated).

An important function of the deltoid in humans is stopping: preventing the dislocation of the humeral head when a person carries heavy loads. The function of abduction also means that it would help keep carried objects a safer distance away from the thighs to avoid hitting them, such as during a farmer's walk. It also ensures a precise and rapid movement of the glenohumeral joint needed for hand and arm manipulation.[2]

The deltoid is responsible for elevating the arm in the scapular plane and its contraction in doing this also elevates the humeral head. To stop this compressing against the undersurface of the acromion the humeral head and injuring the supraspinatus tendon, there is a simultaneous contraction of the muscles of the rotator cuff muscles. In spite of this there may be still a 1–3 mm upward movement of the head of the humerus during the first 30° to 60° of arm elevation.[2]

Evolution

The deltoid is found in other apes. The human deltoid has a similar proportionate size to that of the muscles of the rotatory cuff to apes such as orangutans that engage in brachiation in which it holds the arm when used to the suspend the body. However in common chimpanzees the deltoid is much enlarged weighing 383.3g compared to the human one of 191.9g. In spite of this it is of less proportionate mass to the muscles of the chimpanzee rotatory cuff. This reflects the need in a knuckle walking ape to strengthen the shoulder, particularly the rotatory cuff, so it can support body weight.[2]

The Deltoid is a classical example of a multipennate muscle.

The middle fibres of the muscle arise in a bipenniform manner (like a bird's feather) from the in number, which pass upward from the insertion of the muscle and alternate with the descending septa. The portions of the muscle arising from the clavicle and spine of the scapula are not arranged in this manner, but are inserted into the margins of the inferior tendon.

References

- ↑ Brown JM, Wickham JB, McAndrew DJ, Huang XF. (2007). Muscles within muscles: Coordination of 19 muscle segments within three shoulder muscles during isometric motor tasks. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 17(1):57-73. PMID 16458022 doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.10.007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Potau JM, Bardina X, Ciurana N, Camprubí D. Pastor JF, de Paz F. Barbosa M. (2009). Quantitative Analysis of the Deltoid and Rotator Cuff Muscles in Humans and Great Apes. Int J Primatol 30:697–708. doi:10.1007/s10764-009-9368-8

- ↑ Mnemonic at medicalmnemonics.com 3558

External links

- -691011507 at GPnotebook

- LUC delt

- SUNY Labs 03:03-0103

- Muscles/DeltoidPosterior at exrx.net

- Muscles/DeltoidAnterior at exrx.net

- Muscles/DeltoidLateral at exrx.net

- Deltoid muscle building video example on ExerShare

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||